Is China exporting authoritarianism?

A new report seems to suggest that China is setting up lectures with developing countries to turn them to the Chinese model. But is this a case of misinterpretation or cold, hard facts?

Paid subscribers can listen to an audio version of this newsletter with extra commentary here!

While away on holiday, casual browsing of China news led me to a report produced by the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub entitled “A Global South with Chinese characteristics”. The report argues that:

“As part of Chinese ambition to compete with the existing liberal international order, China has been using political and economic tools to export its model of governance, particularly to the Global South.”

Through analysis of (allegedly*) over 1,000 documents, the report argues that the Chinese government conducted 795 governmental training programs delivered between 2021 and 2022 on commerce, IT, blockchain, etc. with the aim “to directly inject narratives that marry authoritarian governance with economic development—in other words, to promote an autocratic approach to governance.”

Quite a strong assertion, but a concept we’ve actually explored before when discussing China’s attempts at soft power, its piecemeal imperialism, and its influence on foreign media. But do these actions - combined with the above economics training sessions and lectures on computing - constitute an attempt at ‘exporting authoritarianism’? Perhaps the truth is simpler (China is really trying to teach African leaders about blockchain) or more complex (China is trying to teach African leaders about blockchain with Chinese characteristics) or something in between.

Now, it’s worth noting here that the Atlantic Council is a US think tank that apparently promotes ‘Atlanticism’ - “the ideology which advocates a close alliance between nations in Northern America (the United States and Canada) and in Europe on political, economic, and defense issues.” I think it’s safe to say, then, that when reading the report, we should assume that an anti-China slant has been applied to the interpretation of any materials. I also want to add that I hate the term ‘Global South’. It’s not relevant to the discussion, but I just want it noted for the record.

So let’s take a look at the report, and the evidence they’ve provided, and try and gauge to what extent China really is trying to promote their own brand of governance in a bid to outperform the West.

What the report says

As with every think tank report on China, the author feels it necessary to jump back in time - this time to the 1980s - to give context on how everyone could tell China would be a domineering superpower (except for the people in the 1980s, of course):

At the heart of this new push to legitimize authoritarian governance was the example of China’s own remarkably rapid economic development under Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership and an implicit assertion that such successful growth legitimizes not only China’s own autocratic system, but also other non-democratic political systems…

As early as 1985, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping explained, in plain language, that the Chinese political system would resist changes despite economic integration with the world. He told the Tanzanian president at the time, “Our reform is an experiment not only in China but also internationally, and we believe it will be successful. If we are successful, it can provide some experience for developing countries.”

We quickly move on to cover exactly how China passes this experience on to other countries. China apparently uses training sessions to “directly promote ideas and practices that marry economics and politics to make a case for its authoritarian capitalism model”, providing practical steps to help leaders achieve this goal. The courses were hosted by various Chinese ministries, including Commerce, Culture and Tourism, Science and Technology, and Public Security, and ranged from 1 to 60 days in length. They were hosted by prominent figures from the highest academic realms in the land such as the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), most of whom are tainted by their previous statements such as “sometimes people don’t know how their own society should develop, and they need to be guided by strong leaders to show the way” or “Japan dared to release nuclear-contaminated water because it has the backing of the United States.”

Attendees are required to submit a report before each session to explain the current state of their country on the topic at hand (e.g. coastal protection or city planning). This the author deftly interprets as ‘intelligence gathering’:

“Beyond obtaining immediate, updated, and accurate intelligence from foreign government officials, this approach enables Beijing to assess their future willingness to cooperate on that subject… and, most importantly, identifies individuals who are willing to facilitate and build long-lasting relations with China. With this in mind, this research effort focused on trainings aimed at expanding China’s footprint in the Global South’s infrastructure, resources, information operations, and security domains.”

Shocking behaviour.

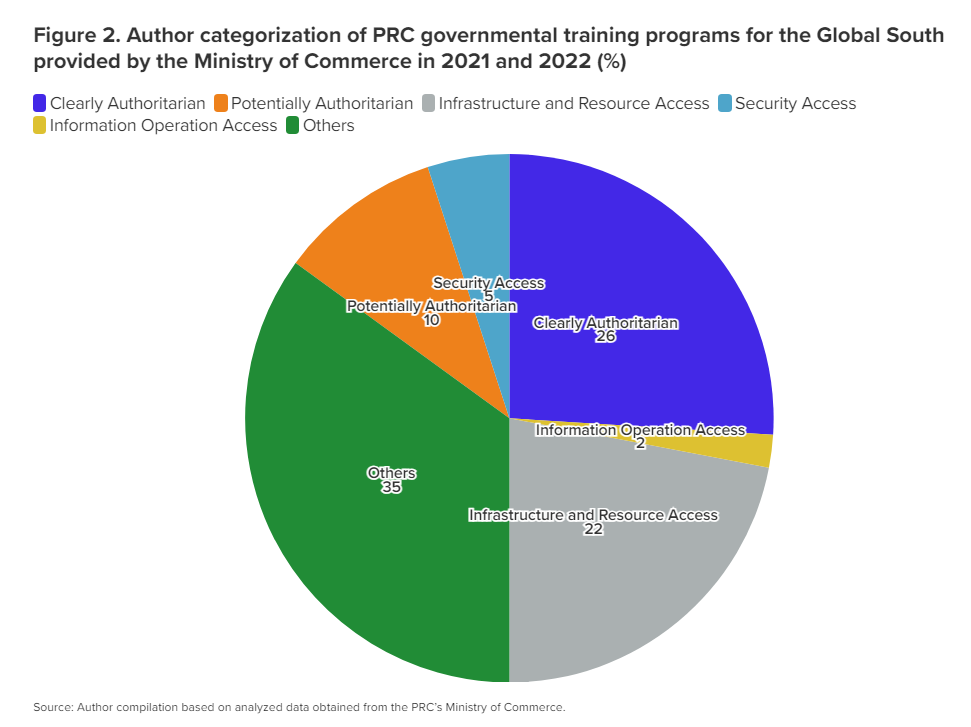

They also neatly categorise each of the sessions to determine what exactly the CCP is getting out of it, whether it’s a direct chance to export authoritarian modes of capitalism, or suss out what resources they can grab in the future. But what the author focuses on is not these more ‘obvious’ cases of promotion, but rather the sessions that fall into the ‘other’ category, which cover issues such as “pest control, climate change, soybean production, tourism development,” etc.

They pull out two sessions in particular: “Seminar on international application of BeiDou and remote sensing,” and “Seminar on port management for Central and Eastern European countries,” which they point out contain “two or three sub-categories [that] are completely unrelated to the training subject, instead focusing on China’s reform and opening-up process, poverty-alleviation programs, and management of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the success of China’s particular governance model in handling these challenges.”

The piece ends with a warning that this proves China is promoting authoritarianism across the developing world, even though

“Beijing often suggests that countries should pursue approaches specific to their own local contexts, rather than adopting the Chinese model completely, PRC trainings clearly highlight aspects of its authoritarian model as central to the blueprint of successful development that others can emulate.” China is evidently keen to continue this practice, opening up a Chinese political leadership school in Tanzania, and pushing ideological lessons in its Luban Workshops.

Even though China’s economy has slowed down, they’re still capturing the hearts and minds of leaders around the world, which irks the writer no end and therefore must be stopped. After all:

“the selective adoption of aspects of China’s system will mean that more countries choose not to align with the United States and other democracies on a range of policy choices that will shape global governance and connectivity… PRC success in encouraging more sympathetic views of autocratic methods—and critical views of democracy—across the Global South would gradually undermine the ability of the United States and other democracies to credibly speak of a common future and interests among countries bonded by democratic values and aspirations.”

Their closing statements argue that to counter China’s positive messaging, negative ‘objective’ information about the ‘realities’ of China should be ‘cultivated’ and ‘promoted’ among local voices, all of which, I’m sure, will be carried out by unbiased, independent parties.

What the documents say

Above, I said that the writer *allegedly looked at over 1,000 documents in researching their report, as this is what they state in the intro. However, at the time of writing only 14 have been publicly released. I have no doubt that they really did spend weeks trawling through them and making elaborate, spiderweb-shaped connections between them, but as only a handful are quoted in the document, we have little to go on to verify the author’s grand conclusions.

Another issue is the lack of information contained within the documents themselves. What we have is essentially a collection of descriptions of training sessions that took place, but no recordings or transcripts of the sessions themselves. We don’t know what was said by the Chinese side, what questions were asked by the participants, or how much authoritarian indoctrination was contained in each session. Were they basic outlines or in depth explorations? Was it 10 back-to-back lectures on Xi Jinping thought, or was the mystery of the blockchain and its possibilities solved?

This exact issue is actually pointed out by the author: “Because this research dataset was limited to program-description files from the MOFCOM, there remain obvious blind spots to understanding the full scope and depth of Chinese governance-export training programs for foreign governmental officials.“

This leads me to my main problem with this kind of piece: if you don’t show all the evidence you have, and lay it all out for everyone to see, you’ll be accused of groundless China-bashing. I haven’t found anything on X yet, but if Chinese officials get hold of the report, the first thing they’ll say is “well, this person didn’t show all their workings out, and they didn’t even attend any of the lectures, so what do they know?” Which is true. We don’t even know who the attendees were! Most of the time they’re just listed as ‘developing countries’, which tells us nothing about the level of seniority of participants, or even if they were government officials at all, or actually what countries they represent.

In any case, it behoves us to at least look at what we do have access to, to see if the author has any point at all despite the dearth of actual info. After reading through the documents myself, I found the 14 at hand could be broken down into 4 categories:

Science and technology development

This encompasses sessions on hard sciences like marine, coastal area planning, geology and geography, as well as IT infrastructure such as big data management, satellite network security, and blockchain. Most of these sessions are open to experts in these fields from developing countries, and their summaries suggest the contents mainly focus on fields of expertise. Many of them appear to include background sessions on “China’s national conditions” including its history, current social conditions, the fight against COVID-19 and poverty. It’s difficult to say how much time and energy was dedicated to these particular sessions, as they would have contained most of the ideological influence the author appears to worry about. The length of each session is not recorded.

Society and population planning

Sessions in this group focused on safe city building, particularly in African countries, and population and development. These sessions seemed to be more advisory, sharing “China’s successful experience of population development and eliminating poverty, providing references for the developing countries,” and potentially promoting the use of Chinese experts and products in the development of future smart cities. These seem more like a promotion of the Chinese model of city building more than anything - use our building companies and materials for a brighter future, and stick some of that tech that we talked about in the other session in there for good measure.

Belt and Road collaboration

Aimed at officials in Belt and Road countries from different areas, including ethnic policymaking, think tanks, and media, with the purported aim of increasing collaboration between China and their BRI partner countries in this area. This certainly could be interpreted as China attempting to have greater influence over thought-development and positive PR along the Belt and Road, though again it’s unclear exactly how this would take place in just a few sessions.

Policy and governance advice

These sessions seem to be construed as ‘learn from our experience’, and contain a lot more about China’s governance model and the CCP than the other session types. Management, for example of ports, universities, volunteer activities, welfare and cities are the major topics at hand. Most sessions seem to contain no more information than will explain how China does it, and that attendees may apply what they learn to their own country’s experience. However, there is some shoe-horning in of China’s own experience with party building, ideological training, and how great Xi Jinping Thought is, aimed specifically at those with influential positions.

Of all the sessions available for us to view, only one clearly stated that it intended to “expand the international influence of the modernized governance system of China.” This one could be interpreted as trying to spread China’s specific mode of governance, as it contained sections on five-year plans, marco-economic planning, and ideological and theoretical training within the party. It was also aimed specifically at those who may have some sway within the government, though only a handful of officials were invited.

While quite a few of the sessions had lectures on China’s national conditions, its past, culture, governance, poverty alleviation efforts and response to the pandemic, the exact nature of this information is unclear. And in some cases, unlike what the author suggests, it could actually be relevant to the topic at hand. Urban planning and information security were questions raised in a lot of countries during the Covid era, and issues such as pollution and coral reef protection are hard to approach when half your population are struggling to feed themselves. The history is often relevant too - how can you understand how to improve your own ports if you don’t know the history of how China improved theirs? (OK, that might just be the historian in me talking, but you get the gist).

Some of the sessions had ‘unlimited’ attendees, but most were limited to about 20-25 participants, not a very efficient way of spreading an ideology. Because most of the descriptions of participants were just ‘officials’ or ‘professors’ from ‘developing countries’, it’s hard to tell if there were any stakeholders present in any of the discussions (only one had ‘presidential advisors’ clearly labelled). Were they university deans or just regular professors with a specialism in big data? Were they financial planners and Chancellors, or administrators and junior executives? It’s almost impossible to tell if the attendees have any influence in their respective countries, let alone what kind of info they were taking back with them if they did.

Verdict

I realise that I’ve struck a rather sceptical tone in this one, and it’s not just because I dislike think tanks and their China pronouncements (though I won’t say that has nothing to do with it). I’m not even really arguing that China isn’t trying to influence developing countries to adopt authoritarian models to exploit bitcoin and get rich or whatever. I’m just taken aback at the lengths the author has gone to stretch out such little information - a thin thread which has now been taken on by the media to spin into shock-value pieces as if it were fact rather than the conjecture of a single researcher who wasn’t even in the room.

Without knowing the actual contents of the lectures, a sensible person would restrain themselves from making such bold assertions (unless, of course, it was their job to do so). A less invested party may be more circumspect. It may be more of a case that China is trying to promote itself and its ideology, rather than export it, a subtle difference. Again, we don’t have access to the training sessions themselves, but even the descriptions seem more to say “China is stable, successful, and has a bright future, which is due to its strong political and economic ideology, here’s what you can learn from that” rather than “hey kid, wanna buy an autocrat?”

I don’t mean to discredit the writer at all, they’ve clearly put a lot of work into this piece. But their preconceptions precede them. And until we can both sit in on one of these lectures and discuss what we’ve seen ourselves, I’m afraid I will remain unconvinced.

Leave a comment with your thoughts on think tanks down below. Feel free to bully, they have a lot of money haha.