I guess we have to talk about Xinjiang cotton...

China-related news has been gripped by stories of Western companies rejecting cotton produced in Xinjiang. We talk China’s cotton industry, Twitter memes, and international relations.

It’s been a crazy couple of weeks on China-watcher Twitter. You don’t even have to search ‘#xinjiang’ to get a barrage of articles praising H&M, a slew of government-sanctioned memes, and angry threads from academics railing against the fact that their research into this slightly political topic has got them permanently banned from China.

For those not in the loop, around 1 year ago H&M made a statement about sourcing products and materials from Xinjiang province, which is available to read here. For some reason, this piece of writing was picked up a couple of weeks ago by the Communist Youth League (of all groups), who railed against the company on Weibo. This led to local brand ambassadors cutting ties with the firm, state media criticising the firm, Chinese social media users calling for a boycott, and online retailers TMall, Taobao, Pinduoduo, and JD.com banning the company from their sites.

The party is now coming for other brands, including Nike, Burberry, and New Balance, all members of the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), a non-profit which seeks to make cotton production sustainable worldwide, and has suspended licensing of cotton in Xinjiang.

This furore is part of the latest development in the larger Xinjiang saga, which began with investigations into human rights abuses against the local Muslim minority in China’s autonomous northwestern province, and which has seen Western governments accuse the Chinese government of genocide against the Uyghur people. While initial stories focused on the development of thought-reform and forced labour camps throughout the province, more recent studies have tried to unveil what happens to those who have been incarcerated once they are released.

So, what is the problem with Xinjiang’s cotton industry? Is this really about cotton supply chains, or about the broader concern over Uyghur welfare that has been developing over the past few years? And how does CCP’s response to allegations over mistreatment affect different actors - from the world’s most powerful governments to humble academics and China researchers?

China’s cotton industry and forced labour

From what I can tell, there has been some conflation of two separate issues: the problem sourcing materials from Xinjiang and the problem of forced labour.

Xinjiang is, indeed, the biggest source of cotton in China (around 80%) and an important source for the global cotton industry (around 20%). The cotton is also reportedly of a higher quality, partly because it is hand-picked as opposed to being machine-harvested, and partly because of the variety of cotton grown. This work is gruelling, underpaid, and usually relies heavily on seasonal migrant labour to fulfil quotas. The cotton industry is also heavily dependent on state subsidies due to the high labour expenditure.

Around a third of the cotton produced is done so under the auspices of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), a paramilitary entity that was established just after the PRC in order to resettle the northwestern frontier and centralise the local economy. They now employ around 12% of the labour force in Xinjiang, and are known to have previously used prison labourers to help pick cotton and reduce labour costs.

It seems that in recent years, in order to bulk up numbers of pickers, the government has concentrated more on local recruitment and “since 2014, Xinjiang has sent a total of 350,000 cadres to villages for 5 consecutive years to help the masses out of poverty and misery and built strong grassroots organizations. [As a result], southern Xinjiang farmers have been effectively organized and devote themselves to poverty alleviation.”

However, researchers have pointed out that because this work is underpaid, the recruitment practices are coercive, and labour transfer schemes may be used to get ethnic minorities to certain areas, this practice of ‘local recruitment’ actually amounts to forced labour. It seems that some retailers are inclined to agree. In their statement, H&M said:

“XUAR is China’s largest cotton growing area, and up until now, our suppliers have sourced cotton from farms connected to Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) in the region. As it has become increasingly difficult to conduct credible due diligence in the region, BCI has decided to suspend licensing of BCI cotton in XUAR. This means that cotton for our production will no longer be sourced from there. Furthermore, in collaboration with the industry and supply chain partners, we will continue our work to strengthen the traceability of cotton.”

Their concern is fuelled by reports “from civil society organisations and media that include accusations of forced labour and discrimination” against Uyghurs. One major source seems to be a report Australian Strategic Policy Institute that has been referenced by many Western media outlets and governments about Uyghur mistreatment and forced labour.

The report states that the Chinese government transfers Uyghurs who have completed their stints in the now famous thought-reform camps to other provinces around the country to work in the factories of major international corporations such as Apple. One conservative estimate states that around 800,000 Uyghurs were “transferred out of Xinjiang to work in factories across China between 2017 and 2019, and some of them were sent directly from detention camps.”

However, the report doesn’t mention cotton specifically. In fact, most reports focus on the fact that many Uyghurs are moved out of Xinjiang to other parts of China, cutting them off from their families. Reports on cotton production tend to focus more on the government’s control over water tables, the quasi-military company in charge of state-owned production who employ mainly Han Chinese, and problems of sustainability and profits for local farmers.

While there are some reports about forced labour in China’s cotton industry, these are fewer and further between, and seem to be reliant on government data about policies such as poverty alleviation schemes. While these schemes can be coercive, they may not necessarily fit everyone’s definition of ‘forced labour’, and it certainly doesn’t count as unpaid labour. If anything, these moves can be seen as an effort by the government to alleviate the poverty and underemployment of local ethnic minorities, who are increasingly worried about the influx of Han migrants to the Xinjiang region.

So, to be clear, I don’t think the problem is the forced labour in the cotton industry specifically, but the problem of forced labour in general. Again, this is part of the general global concern over mistreatment of Uyghurs in China which, yes, for some, could include underpaid labour picking cotton in poor conditions.

I’m not sure why I had to use a whole section just to explain this, but at least some part of me felt that it was important to separate the two issues, as the CCP at least appears to have conflated the two.

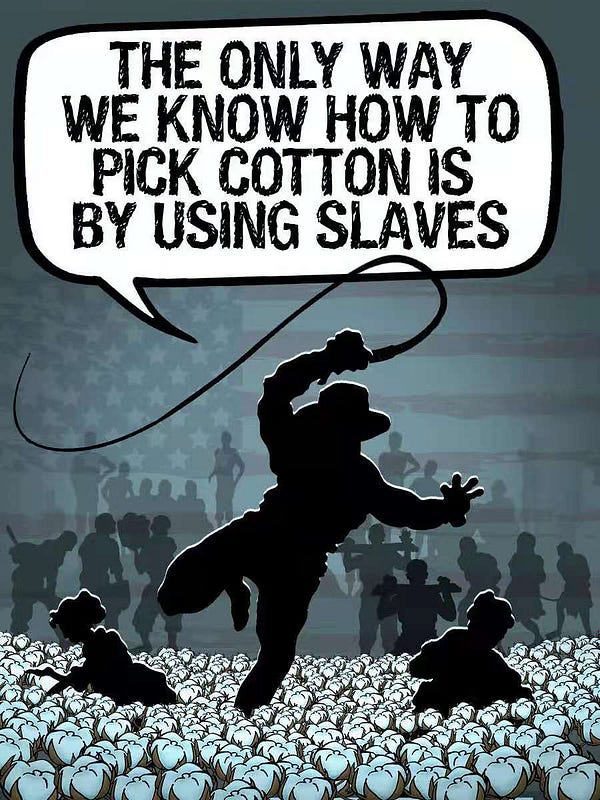

If we take a look at their social media posts, it seems the party believes that H&M and other companies have accused China of using forced labour specifically in cotton production, when I think the issue lies more in the broad sphere of civil rights. Either that, or they’re specifically focusing on the issue of cotton so as to deflect from broader claims about forced labour, and also to bolster their ‘what-about-ism’ arguments about the history of cotton picking in certain countries, which are presented mainly through the art of memes.

So this is how we end up with Twitter posts like this...

Twitter wars

Government approved rap:

“I support Xinjiang cotton”:

A not-so subtle jab:

The propaganda is strong with this one:

It causes me no end of amusement that Twitter is banned in China, and cannot be accessed by the average Chinese citizen, but the CCP and Chinese government work so hard to have a strong presence on this platform. Like, why? Who is your target audience? I think I need to do a newsletter in the future just on the topic of the aims of China’s Twitter diplomacy and why they’re doing it wrong. (For clarity, most governments/political figures are doing it wrong, but not with the bravado of China. And at least their goals are self-evident…)

International repercussions - academia, commerce, and government

This issue has already started to have an impact on international relations. The backlash against certain companies banning cotton produced in Xinjiang is relatively predictable. Landlords have been closing H&M stores across the Xinjiang region.

On March 22, the US Treasury sanctioned two Chinese officials for alleged human rights abuses: Wang Junzheng, the Party Secretary of the XPCC, and Chen Mingguo, Director of the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau. The EU, Great Britain and Canada have all taken similar measures. These claims were rejected by a spokesperson for the Xinjiang government, Xu Guixiang, who said in a statement:

“I don’t think a company should politicize its economic behaviour. Can H&M continue to make money in the Chinese market? Not any more.”

One possibly unforeseen outcome of this uproar, however, is the Chinese government’s retaliation against academics researching and commenting on this phenomenon. Dr Jo Finley, Reader in Chinese at Newcastle University, announced on Twitter on Saturday that she had been sanctioned by the Chinese government for her ongoing research into Xinjiang, which she has been carrying out since 1995. It seems the government has cast its net as wide as possible, and in the process caught anyone with any form of clout who had anything to say on the matter.

Luckily, it seems she doesn’t stand alone. An open letter from academics published in The Times shows solidarity for freedom of research, and reiterates that, unlike in China, British research institutions are not mouthpieces for the aims and ideas of the government.

However, it seems not everybody is so willing to stand with the accused or make accusations against China themselves. The case of the Essex Court Chambers removing the reference to genocide after it had been included in Chinese government sanctions shows how those with interests (and assets) in mainland China or Hong Kong may be resistant to jumping on the bandwagon. We can only hope that China is sincere in its openness to investigation by the UN, which may well take the pressure off of institutions and groups delaying their decision to cut ties with a country that is increasingly becoming many organisations’ most important economic partner.

The bigger picture

It’s important that when talking about individual cases such as that of H&M, we don’t lose sight of the wider issues surrounding Xinjiang and human rights in China. While it’s fun to zero in on ridiculous tweet wars and tit for tat sanctions, there is a human cost being paid while all this uproar is taking place.

A research piece by Joanne Finley - the academic sanctioned by the Chinese government - rightly highlights issues far beyond that of coerced labour. Entitled Why Scholars and Activists Increasingly Fear a Uyghur Genocide in Xinjiang, it discusses forced sterilisations, mass incarceration, and cultural genocide practices such as forcing Uyghurs to “to abandon their native language, religious beliefs and cultural practices.” Her research shows that more people are coming round on the term ‘genocide’ when it comes to the Uyghur population, including international legal experts, governments, and academics in a range of fields, many of whom were reluctant to speak out initially.

Moreover, her being sanctioned by the CCP highlights an important point about long-term research into Xinjiang and possibly China in general: the longer this issue goes on, the more restrictions will be placed on researchers, and the more the door will be closed on foreign observers trying to get a grasp on welfare and rights issues in China.

Sources

Apparel Insider, Xinjiang, XPCC and the sham of ‘sustainable cotton’

Australian Strategic Policy Institute,Uyghurs for sale

CNN, H&M and Nike are facing a boycott in China over Xinjiang cotton statements

The Guardian, UN in talks with China over 'no restrictions' visit to Xinjiang

H&M Group, H&M Group statement on due diligence

Joanne Smith Finley, Why Scholars and Activists Increasingly Fear a Uyghur Genocide in Xinjiang

Newlines Institute, Labor Transfer and the Mobilization of Ethnic Minorities to Pick Cotton

Quartz, A year-old H&M statement about Xinjiang cotton is getting fierce blowback in China

Shangye xinzhi, Notice about doing a good job with seasonal labor work such as picking flowers (关于做好拾花等季节性劳务工作的通知)