China's biggest soft power flop

Confucius Institutes were once the boogeymen of the China-hawk brigade. Now they are a forgotten relic of China’s soft power push.

In the book Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist is Reshaping the World, the authors describe Confucius Institutes as “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda set up” that “facilitate spying”, "suppress academic freedom” and “exert pressure on smaller players”. Now, if you couldn’t guess from the title, the book is rather inflammatory in some places. It’s not necessarily that what the authors are saying are untrue, but rather slightly exaggerated (in a few cases they describe certain parties as being ‘cowed by fear’ into submitting to the CCP’s will, when it sounds more like greedy capitalists trying to protect their bottom line, but I digress).

The point is the rhetoric in this book is part of a larger discourse surrounding not just Confucius Institutes, but the Chinese state’s attempts to spread Chinese language and culture more generally. As the book points out, by the time of its release in 2020 many of these institutions had been closed down, had their funding stopped, or came under investigation following investigations or concerns raised by academics and students. And yet the perceived threat of China’s ‘hidden hand’ in society – whether via social media or news outlets or some other means – is still pervasive.

I recently published a podcast episode discussing China’s dearth of soft power, its causes, and the consequences for China geopolitically. In that episode I spoke in depth about theories of soft power, and how an attractive ideology and universalistic language that resonated with people no matter where they are from were so key to developing it. Confucius Institutes were undoubtedly Part of China's soft power push, but have now largely failed, particularly in the West.

For those who have never heard of them, Confucius Institutes (CIs) were run by a branch of the Ministry of Education called Hanban, but have since been ‘decentralised’ and put under the management of Centre for Language Education and Cooperation (CLEC) (also Ministry of Education, so make of that what you will). The CIs themselves are usually run in collaboration with a local university or other host institution. At their peak in 2023 there were 496 CIs and 757 Confucius Classrooms (CCs) worldwide.

But by the 2020s suspicions grew and a crackdown began, particularly in Western nations. In the US, amidst increasing tensions with China, 104 of the 118 have been closed or had their funding stopped; in the UK funding has all but ceased and existing CIs are relegated to the Asian Studies departments of a handful of universities; and in Europe the backsliding is gradual but apparent. India, the world’s second most populous nation and China’s neighbour, has only 2 institutes in the whole country. This is a huge blow to one of China’s major soft power arms.

Why soft power matters and the (wasted) potential of CIs

As comments on my latest episode show, people’s feelings towards soft power vary greatly. For many people it's apparently completely useless, especially for a country like China which has so much economic influence. Or, allegedly, China has so much soft power in places like South East Asia and Africa already that it does not require developed or Western nations to accept them for who they are.

But I disagree with these takes. Soft power is not just useful, it's fundamental to a nation's growth and success on all fronts. I also disagree with the idea that what China has now is anything amounting to decent soft power pretty much anywhere.

First of all, financial success, in the broad sense, is not the same as soft power. While it's true that having strong brands that are trusted around the globe can contribute to a country's soft power (Starbucks, Samsung, Suzuki, other S brands), money can't buy soft power. At least not directly. Despite investing millions in development banks, trade funds, media, sports and arts projects globally, in the words of David Shambaugh: “What is striking about China’s investments is how low a return they appear to be yielding. Actions speak louder than words, and in many parts of the world, China’s behavior on the ground contradicts its benign rhetoric.”

Secondly, soft power should not be limited, geographically or otherwise. It should be diffuse and imperceptible – we shouldn't even be able to tell that China's soft power is stronger in some places than others. Just like English language ability, one takes it for granted that most tourist hotspots will have a little English to cater to international tourists, native English speakers or not. We take it for granted that some of the highest rated TV shows on Netflix might be Korean, or that kids TV channels may show dubbed Japanese cartoons just as often as a Hannah Barbara production.

I agree that a lot of soft power is a hangover from colonialism, and part of grander neo-imperialist projects, particularly the diffusion of the English language globally. It's undeniable that the US’ soft power is intrinsically linked to its hard power – its military prowess and economic might. But the point is that China's soft power is not yet interwoven with its hard power, which is why it comes off aggressive, suspicious or clunky when making geopolitical moves. You may not think China should need soft power, but at the end of the day if it wants to be the next global superpower it does need it.

And it’s clear that China believes this too. Apart from the myriad language programmes, China has multiple expos a day across the country, hosts numerous outreach programs, and funds media outlets and journalism training schools all over the world working to improve China’s international image. These are not the actions of a country uninterested in its global image or unaware of its importance.

Looking at the CI website, it’s clear that there are many institutes around the world still going strong, especially in developing nations with which China is pushing to improve relations. But to be honest, the actual number of CIs is not the yardstick with which we need to measure the success of their mission. At the end of the day, if the role of CIs is/was to increase Chinese language enrollment worldwide, we need to know how well they’ve fared.

According to the 2024 Annual Report CIs have over 20 million students worldwide. But how many of them are continually actively engaged in the continual study of Chinese language and culture?

Admittedly, this is hard to pin down. Many nations do track language learning enrollment at various levels, but getting a global picture is a bit harder. But we can paint a bit of a picture by piecing different stats together. For example, in the US at university level:

“Total college and university enrollments in languages other than English dropped by 16.6% between fall 2016 and fall 2021... Of the fifteen most commonly taught languages, only three showed gains in enrollments: American Sign Language (0.8%), Biblical Hebrew (9.1%), and Korean (38.3%).

The decline in the number of programs occurred among both commonly taught languages and less commonly taught languages (LCTLs). German declined by 172 programs, French by 164, Chinese by 105, and Arabic by 80… the most notable finding of the 2021 census is the staggering loss in enrollments that most languages experienced… [for] Chinese/Mandarin (14.3%).”

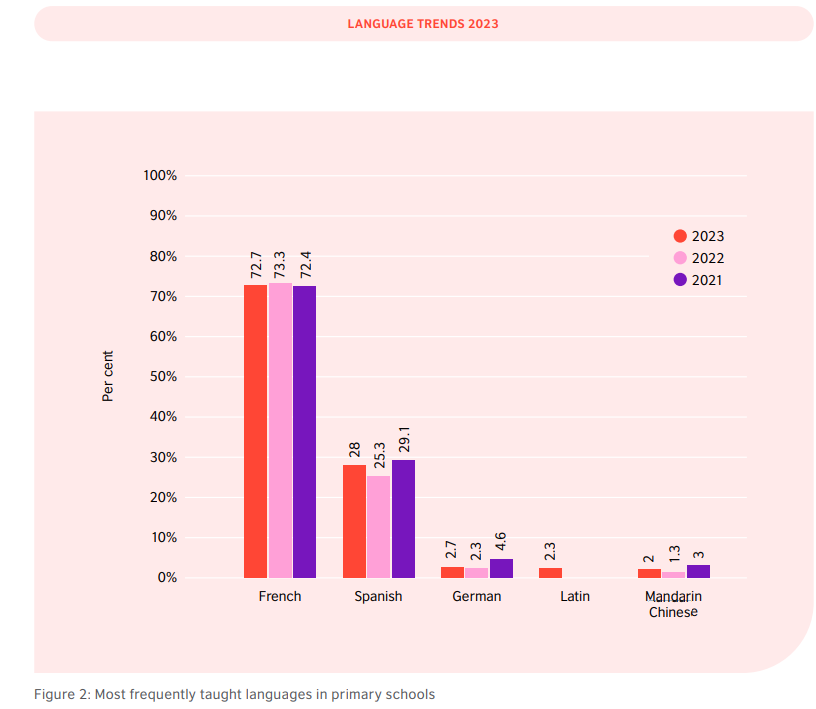

In the UK at secondary (high school) level, Chinese is the most popular language taught as a full curriculum subject after the ‘Big 3’, but uptake still lags way behind despite promotion through the “Mandarin Excellence Programme”:

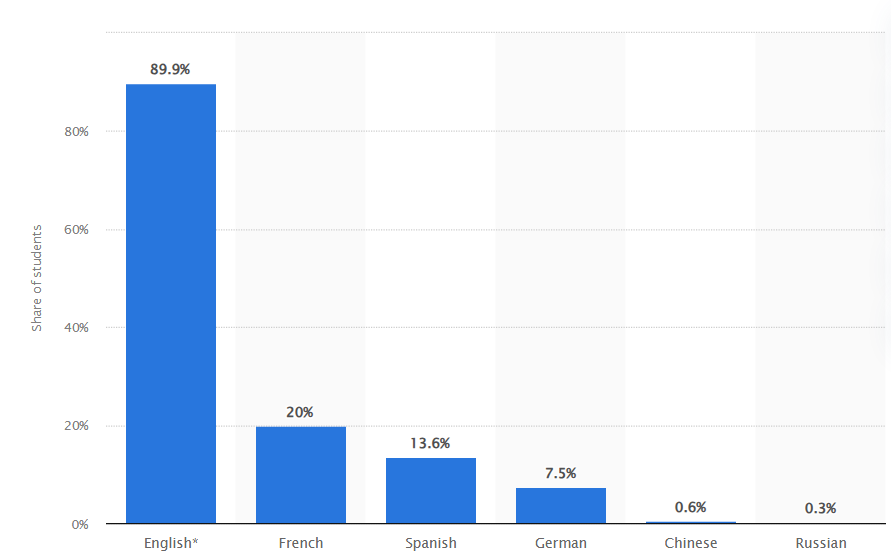

In the EU, where students study at least one language from primary age and most people can speak more than one language, interest in learning Chinese is abysmally low (less than 1% of young people in many countries). Even in places like Italy, where there is some interest, only a small share of high school students study Mandarin:

Even in Southeast Asian countries, where there are large numbers of Chinese diaspora in countries like Singapore and Malaysia, there has been a lackadaisical attitude towards a country that has such a strong presence both economically and socially. Most national education systems are in English, and Chinese is taught as a second language even in areas where there are high numbers of ethnic Chinese. Where there are Chinese higher education institutions, many of them offer schooling in English instead of Chinese. According to ISEAS Singapore:

Due to the “nationalisation” of Chinese schools by many Southeast Asian states, the standard of the Chinese language among ethnic Chinese have [sic] gradually declined. With the exception of Malaysia and Laos, most “Chinese schools” have been transformed into local schools that offer the Chinese language only as a subject taught for several hours a week. Many of their teachers are not well qualified and there is no conducive environment for ethnic Chinese children to learn the Chinese language. Anti-China and anti-ethnic Chinese attitudes in many countries in the region have also impacted Chinese language learning.

The picture is worse when compared to other East Asian languages. Comparing enrolment in Chinese language courses vs increasingly-more-popular language courses (for example Korean or Japanese) is an imperfect metric when trying to measure China’s soft power. But it actually works pretty well as a proxy if put into the context that China was once making active efforts to promote Chinese language learning across the world, so we’re gonna use it anyway.

Going back to the UK, despite a push at primary and secondary levels, Chinese language learning drops off at university level, only to fall behind Japanese:

The two largest courses in this group – “Chinese Studies” and “Japanese Studies” – have experienced contrasting outcomes. Acceptances to “Japanese Studies” have increased by 79% over the period, with the sharpest rise taking place in 2015, followed by a slight dip and steady rise again since 2017. In contrast, “Chinese Studies” has decreased by 41% since 2012. This is interesting when one considers the emphasis placed on Mandarin Chinese in some schools in recent years with initiatives such as the Mandarin Excellence Programme as well as the strategic importance of this language for the UK government.

According to Duolingo, in countries where interest in East Asian language learning is highest, Korean and Japanese continue to outpace Chinese.

While a casual language learning app is not the best indicator of overall adoption or proficiency in a given language, it does point to something deeper: organic interest in Chinese language learning is still behind that of East Asian counterparts. Despite the fact that China probably has the most to offer anyone looking to invest, work with, or relocate to one of these countries, people are still more organically attracted to learning Japanese or Korean in their free time.

Hanyu Qiao and what CIs actually do

While researching the role of CIs and their successes and failures, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own journey with Chinese and time living in China. What possessed me to spend the best part of a decade studying the country’s language, history and culture? Surely it wasn't just the allure of a highly paid job in a think tank spinning yarns about the world’s next global superpower (please note the author has never had a high-paying role ever, Chinese skills notwithstanding).

I can no longer pinpoint the origin, but I think my attraction to China grew steadily over time, only after being introduced to Chinese culture cursorily through Ang Lee movies, adding new bits and bobs to my education till I finally got to the point where I actually entered Hanyu Qiao or Chinese Bridge (or was entered by my university? My memory fades). I wasn’t the best at Chinese in my class, nor were the other two girls who were entered (although one of them did go on to get 1st place). I think we were chosen more for our general compliance and pleasantness, and for the fact that we all looked pretty good in a qipao.

We were prepped for about 2-3 weeks at the university’s CI by two dedicated teachers, memorising our speeches, practising ‘cultural performances’, and answering practice questions. Once we were done with the competition and got our certificates (I came 3rd :D), that was the last time I ever saw them. I don’t remember anything about them, nor could I tell you where the Edinburgh CI was located if you held a gun to my head.

Despite having done an Undergraduate, Masters and PhD in Chinese related degrees, this was my only real experience with a CI ever. This is bearing in mind that I was an already engaged audience – I had gone out of my way to learn Chinese, live in China, engage in the culture. My cohort were the perfect targets for a coordinated soft power push. And yet apart from the occasional invite to a New Year’s meal or … actually that’s it, I can’t think of anything else, we never really heard from them.

There was no energy or passion behind their supposed mission. This could be because the institutes are staffed by centrally approved, high-achieving, proficiently trained teachers. But as is often the case, these sorts of people don’t make the best missionaries. This is not to denigrate their teaching at all – they were incredibly dedicated and hardworking, but they lacked the vigor required to inspire and push you beyond your comfort zone. When it came to the Chinese Bridge prep, the environment was formal and the process frankly quite boring and time consuming.

Looking back, this was clearly a fumble of major proportions. Students like me and the other 15ish people on my course should have been primed and ready to spread the good word of Chinese culture. By the time we graduated, we should have all been lining up to spend a lifetime working either promoting Chinese culture and language in our home nations, or working in China helping to figure out how to successfully promote the CI mission abroad. But as far as I can tell, most of us don’t even work in China-related fields (ignore this newsletter, I just write this for fun).

I know this part is just my personal experience, but it seems wild in retrospect that I will actively engage in Korean culture in my free time, whereas I have to almost push myself to keep up to date with China, and have actively let my language skills slip to shocking levels (probably couldn’t hack a HSK5 at this point), considering how much influence China had on my life for over a decade. I still maintain a podcast about China, but sometimes I wonder how much of this is out of a weird sense of guilt or necessity; a sort of sunk cost fallacy more than a genuine sense of love from which ideas and words flow easily.

Of course a large part of it is personal faults and failures, and everyone’s experience will be different. But I do still believe that on a grander scale, this is a reflection of the ambivalence of China’s soft power and a failure to fully engage an active audience to build up the Chinese mission abroad. But perhaps there still is room for CIs to influence the next generation of Chinese learners, if they can learn from the success of others.

A possible pivot

Ironically, for the CIs to have had the best chance of success, China needed to already have a strong soft power base. This way, the CIs would have worked efficiently as the linguistic arm of China's global expansion, not unlike the British Council in the UK.

Now would probably have been the best time to launch them. With the active retreat of the US from global diplomacy, increased trade networks, and more recognisable global brands that appeal to all demographics from BYD to Labubu, China is in a stronger position than ever to launch huge cultural projects. But if they do intend to do a relaunch at any point, serious rebranding is necessary.

I would probably opt for a name change first and foremost, not just because of the bad rep of CIs past, but because while the connotations of Confucius Institute name are obvious, it gives off a stale and stoic vibe that I can assure you any time spent at these places reflects. The “we <3 China” vibes are so overt as to be off putting for all but the most die hard fans, who already <3 China. China is more than calligraphy, Hanfu, and reciting stolidly translated thousand-year-old poetry, and while I’m no branding expert, I’m sure a new name could reflect a refreshed mission.

This rebranding would bring in line with soft power tactics of countries like South Korea and Japan, which rely heavily on the organic spread of pop culture, which naturally contains cultural teachings just by their very nature. Once certain elements have been absorbed (through film, dramas, music or literature), they can be built upon with more formal teachings to reinforce the context of the culture.

Finally, the content of what the CIs offer also needs to be updated, as well as those delivering it. The teaching materials need to appeal more organically, using modern media and materials that never utter the phrase HSK, and connect with people’s existing interests such as travel, social issues, news and politics. They need new staff that are just as interested in the place they've moved to as they are in China, and to avoid the evangelical missionaries who only push the gospel.

This is an impossible ask, but for the future of CIs to work, the state needs to let their development be messy, informal, and unfettered. Remove the strings of the state, and create a new institution that can be a true representation of China that those who discovered it on their own know and love. One that thrives in spite of central doctrine, not because of it.

Unfortunate on all levels:

1) the Chinese learning material distributed by the PRC is the absolute worst. I am not talking about insidious infiltration here, I am talking about boring, clunky and totally interest-killing in all respects. Here’s looking at you, 济南大学 textbooks.

2) the outlandish levels of suspicion directed at CI programs ended up being an own-goal by the West. They got shut down without any replacement funding so, now we are training very few Chinese-speakers when PRC is supposedly our biggest rival.

3) my kids also go to a school that had a good Chinese program originally funded by CI but isn’t any more. The school is now struggling w funding but also with enrollment since the admins don’t really understand bilingual education or how to promote it, and a few parents in the district who wouldn’t know a Chinese character if it bit them are showing up at school board meetings “worrying” about a) bathrooms b) “Communist” teaching material.

4) My high school Spanish teacher was obsessed with Julio Inglesias. We listened to him in class, learned lyrics to his songs, his posters were on the wall. I emerged with OK Spanish and haven’t given one thought to Julio in the 30 years since. Any CI attempts at indoctrination could have been just as easily shaken off.

5) it was very dumb of (a very few) CIs to attempt to get involved in issues like the Dalai Lama visiting a college campus. But also college administrators could and should have just told them no, end of story.

A brutally frank and important article. As you point out, you can't buy soft power with money. The Chinese government needs to realize that soft power is a bottom-up phenomenon, not top-down. I know some American professors who used to collaborate with CIs in the US, while CIs still existed. From what I learned, it seems the CI budgets were boundless. The professors would ask for, say, 50 textbooks, and would receive 150. As big as their budget was, they were quite stingy in paying their teachers, and thus had a high turnover rate. I participated in some CI events in Ann Arbor, University of Michigan. Most of them were embarassingly propagandistic, cloyingly shallow, and inevitably presenting the usual calligraphy, paper cutting, and classical poetry memorizing. I met a couple of young men who worked for Hanban in Beijing. They told me about some computer/AI multmedia teaching tools they were developing. I expressed an interest in seeing this technology, and they promised to invite me to the Hanban HQ near Deshengmen for a demonstration. Time went by, and they never got back to me. When I contacted one of them to ask when I could visit the building, they told me the organization didn't want to give demonstrations of technology that was still in development. I haven't heard from them since. They obviously don't need more money. They need more creativity.